It was a Monday morning. I remember that because Mondays are usually when I make my calls, text message orders, and inquiries for the week, lining up the wild and farmed fish and various other seafood products for the restaurant’s menu. Like the availability of fresh vegetables and fruit, fish is a highly seasonal game. It’s dependent on the weather, people’s schedule, and increasingly, the cost of fuel and scarcity of labor. Another sip of coffee and I shrug off some of those worries I have about finding enough local fish for the week. At this point, only 3-4 months into the great endeavor of trying to source 100% directly from fishermen and I still did not have enough partners to complete the turn of our annual menu. But the Pacific is large, I tell myself, and I will find the right people if I just keep at it.

I started with something familiar, something I knew was a solid winner for me, even if it wasn’t going to bear new fruitful connections to the commercial fishing world. I rang up Monterey Abalone Company. A solid, and I mean really solid, company. I always like calling them because oftentimes I get Art Seavy on the phone, or his business partner Trevor — crusty old barnacles who have been working there on the commercial wharf in Monterey for the last 30 years. They have seen all of the evolutions in the California fishing industry, and they are lucky enough to be able to continue their farm. Growing abalone in cages sunk almost to the seafloor amongst the wood pillars that hold up the wharf. In the wake of the Pandemic, they have witnessed historic demand for their product as fine dine restaurants came back on board all at the same time, throwing their annual farming production calendar into a catch-up pace that they are not accustomed to. Demand is high, prices have increased across the board, and they are working too much. Isn’t life a piece of work?

Art picked up the phone. He has this roaming, quasi-perplexed kind of tone to his voice, as if you are always distracting him from some deep thought or a long gaze fixed on the Big Blue. I placed our usual order of 50 pieces of quarter pounder abalone for the week, and just before he slammed the phone down, I sheepishly asked him if he knew of any fisherman still operating actively out of the port of Monterey.

Hesitating at first, I could tell that Art was racking his brain for names, perhaps people he knew from the past that may or may not be still fishing. At any rate, it was not anything resembling an immediate response. He fumbled a bit, and then coughed up a name that sounded like “Jerry”, but with more emphasis on the “E” making it sound like an “I”. Art promised to have a phone number available for me the next time I called. The mysterious “Jerry”.

A couple of weeks later, I drove down to Monterey for a planned face to face meeting with Jiri Nozicka (pronounced “Jeer-ie”). Art had told him that I was looking for a fisherman to work with directly. And Jiri is, well, a fisherman. He is actually the OG kind of fisherman that you don’t encounter much anymore. He’s the real fucking deal and his story is symptomatic of the struggles and complexities of being a fisherman on the coast of California in our modern era.

I pulled my van up to where the series of consecutively interlinked warehouses built atop of the extended Monterey wharf begins (this is a quarter mile out into the Monterey Bay above the water line, for those that have never had the pleasure). It’s breathtaking turf to say the least, with sandy dunes lining a deep blue oceanscape as far as the eye can see. Cringing, as I slowly crawled along the narrow corridor of the sidelane of the wharf, for a moment, I cursed the logic in this proposed meeting site. While avoiding the thought of my car losing its grip and dropping like a shipping container blown off the side of a tanker into a cold watery abyss, I was relieved by the notion that something at the end of this journey was worth the risk.

My van rolled up behind a vintage 80s pickup near the end of the line, where Jiri keeps his cold storage and office. Jiri’s boat, the 80 year old wood hull drag netter named the San Giovanni, lies 50 meters out in the heart of the port of Monterey. Stuck somewhere in a time warp between the ageless ocean and the throngs of modern ocean vessels anchored neatly within the port’s jetty. “Thump, thump, thump.” A meaty hand bounced off of my passenger side window. It was Jiri. He was signaling me to enter his warehouse. Our hands connected in the usual introductory shake. Mine, the delicate dainties of an artist subjected to 20 years of forced abuse in the kitchen. His, the fleshy mitts of a man who is used to digging out crushed ice with his fingers, nails inset almost as admission of their desire to retreat from the wanton abuse. This was the beauty and the beast of hand meetings. A trope that I have experienced and continue to repeat all up and down the coast, almost every time I meet someone of the trade.

Jiri is a Czech national. He made his way to Monterey after a visit with his brother some 25 years ago and fell in love with the water. The San Giovanni, where Jiri worked as a dayboat fisherman for some time, is a relic of the past. Constructed in the 1940s out of solid wood, this boat bears that charmed romanticism of a bygone fishing era. Imbued with a rugged masculinity, conjuring in my mind passages from The Old Man and the Sea, hard drinking men who work hard too and Great Depression era human tragedy. If the San Giovanni were a man, it would be John Steinbeck, Ernest Hemingway, or Jack London.

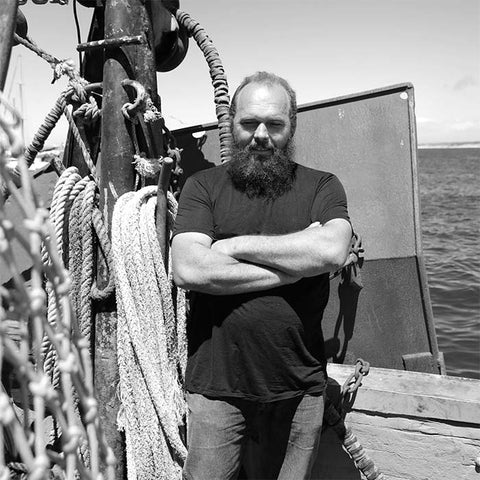

Despite all of that, Jiri has the artistic meanderings of a poet and the physical aspect of a rugged farmer. Stout in his stance, he is half bald, but with a curly, raspy black beard that hugs his chin like a poodle’s mane. He screams old world Czechoslovakia — a poor farmer from the Eastern loc — but his words and outlook are pegged to another century and a vastly different part of the world.

We got right into talking shop. Jiri has been out of the fishing game for eight years. The entire port of Monterey went into decline after a wave of strategic fishing zones in the area went under the protection of the State of California and the Federal Government, causing the warehouses on the wharf to shut down. Conveniences such as readily available ice, fueling stations, storage space, and a market ready to sell the bounty of a catch disappeared overnight. Jiri turned to trades like construction to pay the bills, but his passion remained in the throws of operating that old boat on the open ocean. A man passionate about skate and petrale sole, a man who fills volumes in elucidating the differences between cow cod and vermillion cod, a man who upholds that the ling cod is a firm rival to the Atlantic cod, and who speaks with glowing praise for the revered sweet flesh of the sanddab as the best of what the Pacific has to offer.

Jiri has fixed up the old boat, needing several thousand dollars to get the hull resealed and some of the old sidewinder arms repaired. Transfer of the title and permit took several years due to a purposefully slow administration process that seeks to keep fishermen off the water as a means to protect the resources of the ocean. We talk about this and the politics around fishing, for which Jiri has some of the most nuanced opinions I have ever heard — and I have heard it from everyone. He has waited patiently over the years for his moment to return to the ocean and so we talk about ways in which we can work together in the future as a guaranteed place to land his fish.

Jiri represents one of the last remaining working boats out of the port of Monterey, other than the occasional squid boat. So his determination to get back into fishing is a ray of hope in the storm ravaged skies over the coast of California’s perverse fishing laws and regulations.

We parted ways that day the same way that we met — a solid handshake affirming the mutual hope that one day we will work together. And now several months later, I am Jiri’s most important restaurant partner — and I never miss the call to come down and pick up when he brings in a boat full of fish. Captured by the romance of a boat that is twice as old as I am, I am determined to see boats like the San Giovanni parade along the shoreline of California for many generations to come.

Peter J Hemsley